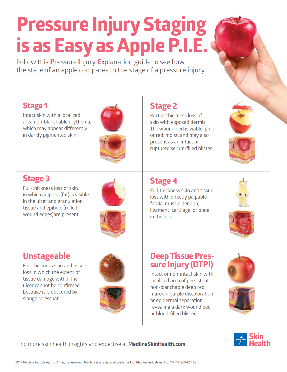

Despite extensive pressure ulcer prevention programmes, pressure ulcers remain a problem that costs the National Health Service (NHS) around £1.4 million every day, with more than 1,300 cases a month.1 Many of these cases are preventable if simple knowledge is shared and preventative best practice is followed.2

There is a large number of risk factors to consider, such as immobility, surface, friction and shear, but Beekman et al. (2014)3 argue that moisture is a key risk factor that should be taken more seriously. Their systematic review and meta-analysis of incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) indicate that individuals with bowel and bladder incontinence and related IAD are 4.9 times more likely to develop pressure ulcers than continent patients.

This is also supported by Lachenbruch et al. (2016),4 who conducted an analysis of data on incontinence and hospital-acquired pressure ulcers from the International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence (IPUP) survey.

In addition, Coyer and Campbell (2018)5 found that, due to the nature of their acute illness, critically ill patients are predisposed to have acute faecal incontinence with diarrhoea (AFID), thus making them high-risk cases for developing IAD. This is also reflected by Wang et al. (2018).6 They reported the incidence of IAD in intensive care units (ICUs) to be an estimated 24 per cent. In fact, IAD has long been recognised as the most common form of moisture-associated skin damage (MASD).

Valls-Matarín, et al. (2017) further showed it is not just IAD but also intertriginous dermatitis (ID) that affects critical care patients. In their study, they showed the prevalence of MASD (primarily IAD and ID) amongst patients staying >48 hours in ICUs was 29 percent. In addition, the most common location for ID was in the intergluteal cleft, which is also a common pressure ulcer point.7

Given the evaluated risks of pressure ulcers linked to moisture, NHS Improvement and NHS Stop the Pressure have now made it best practice to record incidents of MASD in the same way as pressure ulcers.8

Reduce the risk of moisture-associated damage in 3 simple steps

STEP 1 – Cleanse the skin

Cleanse the skin thoroughly to remove all irritants, including bodily fluids. When exposed to urine and/or faeces, the skin’s pH changes, and this causes an increase in permeability and a reduction in the natural barrier function. Cleansing the skin also ensures the natural function of the skin is maintained (Wounds UK Best Practice statement, 2012).

Following cleansing, ensure the skin is completely dry.

STEP 2 – Keep excess moisture away from the skin

Where there is the risk of exposure of the patient’s skin to excessive moisture and fluids, place an appropriately sized Ultrasorbs Drypad under their body. This will absorb and wick away the moisture, helping to keep the skin dry.

STEP 3 – Protect and moisturise the skin

Apply a moisturising barrier cream and/or film to moisturise and protect vulnerable skin, creating a physical barrier and minimising exposure to irritants and excessive moisture, such as bodily fluids.

New protocol for the prevention of incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD)

A quality improvement programme was introduced at Sandwell and West Birmingham’s critical care unit, which includes guidance on ‘The Management of IAD for critical care service patients with loose stool’.

Within these guidelines, Fisher and Himan (2020) recommend protecting patients’ skin with a skin barrier cream, in conjunction with an Ultrasorbs drypad, which wicks moisture away from the surface, keeping patients’ skin dry.

Medline resources to support the national ‘Stop the Pressure’ programme

Medline’s Ultrasorbs Drypads Moisture Management System

This moisture-wicking technology makes moisture management as easy as ABC.

A

Absorbs more of a patient's

bodily moisture

B

Breathes more to optimise the skin's microclimate

C

Contains more bodily fluid, reduicing the number of full linen changes

Vicky Hogg

Product Manager Regional, Medline UK

Vicky has over 25 years of experience in the UK healthcare industry. Graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in psychology and communications, she joined the pharmaceutical industry, working in primary and secondary care for 5 years. Vicky later moved into medical devices where she has had a range of product specialist roles over the last 20 years.

References

1. https://nhs.stopthepressure.co.uk/index.html

2. https://www.england.nhs.uk/atlas_case_study/react-to-red-reducing-pressure-ulcers-in-care-home-settings/

3. Beekman et al, 2014, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/nur.21593

4. Lachenbruch C, Ribble D, Emmons K, VanGilder C. Pressure Ulcer Risk in the Incontinent Patient: Analysis of Incontinence and Hospital-Acquired Pressure Ulcers From the International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence™ Survey. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2016 May-Jun;43(3):235-41. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000225. PMID: 27167317.

5. Fiona Coyer, Jill Campbell, 2017, Incontinence‐associated dermatitis in the critically ill patient: an intensive care perspective, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/nicc.12331

6. Wang et al (2018): Incidence and risk factors of IAD among patients in the intensive care unit. Journal of Clinical Nursing. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/jocn.14594

7. Valls-Matarín, et al. (2017). Incidence of moisture-associated skin damage in an intensive care unit, 28(1), 13–20

8. NHS Improvement (2018). Pressure ulcers: revised definition and measurement: Summary and recommendations